Agnolo Bronzino (Florence 1503-1572), Portrait of a young man with a book, oil on poplar panel, 37 x 30¾ in. (94 x 78 cm). Estimate $8,000,000 – $12,000,000. Photo Christie’s Image Ltd 2015

Provenance: Corsini Collection, Palazzo Corsini, Florence, by 1842.

Private collection.

Literature: F. Fantozzi, Nuova guida, ovvero descrizione storico-artistico-critica della citta e contorni di Firenze, Florence, 1842, p. 556: ‘Uomo che scrive. di A. del Sarto’.

G. François, Nuova guida della citta di Firenze ossia descrizione di tutte le cose che vi si trovano degne d’osservazione con pianta e vedute, Florence, 1853, p. 150: ‘Uomo che scrive, di A. Del Sarto’.

U. Medici, Catalogo della galleria dei Principi Corsini in Firenze, Florence, 1886, p. 17, no. 17: ‘CARRUCCI JACOPO (detto il Pontormo) – Ritratto di uomo in costume fiorentino del Secolo XVI. – mez. fig. gra. nat. Tav. al. m. 0,94, lar. m. 0,78’.

F.M. Clapp, Jacopo Carucci da Pontormo, New Haven and London, 1916, pp. 202-203, no. 17, as not by Pontormo.

C. Gamba, Il Pontormo. Piccola Collezione D’Arte N. 15, Florence, 1921, pl. 45, as Pontormo.

J. Alazard, Le portrait Florentin de Botticelli a Bronzino, Paris, 1924, p. 177, n. 2, as school of Pontormo.

C. Gamba, Contributo alla conoscenza del Pontormo, Florence, 1956, p. 16, as Pontormo.

Fifty Treasures of the Dayton Art Institute, Dayton, 1969, p. 70, under no. 21; p. 133, fig. 5, as not by Pontormo.

P. Costamagna, Pontormo, Milan, 1994, pp. 310, 311, no. A91.1 as a copy or replica of the ex-Lanfranconi picture.

C. Falciani, « Spigolature sul Bronzino (e sul Pontormo) », Paragone, CXI, September 2013.

The present portrait will be published in Dr. Elizabeth Pilliod’s forthcoming monograph with a catalogue raisonné of Bronzino’s drawings and paintings, as datable to c. 1525, possibly Bronzino’s earliest surviving portrait.

Dr. Janet-Cox Rearick has also confirmed the attribution to Bronzino on the basis of firsthand inspection.

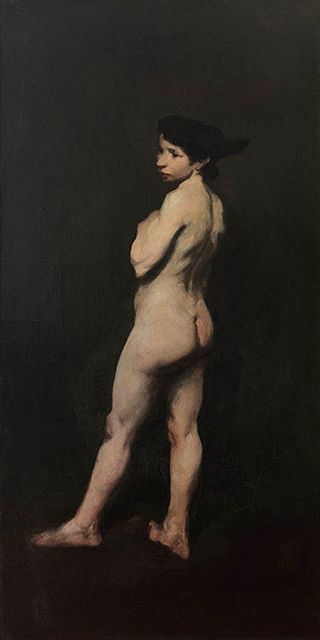

Notes: Portraiture, especially prior to the advent of photography, served numerous functions, among them recording a likeness for posterity, conferring status and authority, celebrating events such as a betrothal, marriage or receipt of an honor. And of all the genres, perhaps no other is so aware of its own tradition. Portraiture flourished in Ancient Rome and, while never extinguished, was revisited with renewed enthusiasm in the Renaissance all over Europe. Indeed some of the most recognizable images of the Renaissance–most notably the Mona Lisa–are portraits. From Titian a sub-genre of ‘swagger’ portraiture developed, a torch which would be passed on from him to Van Dyck to Reynolds and on to Sargent and eventually to Lucien Freud whose Brigadier (fig. 2) subversively echoes the glamorous officers and imperial heroes painted by the earlier masters. From Tuscany a different thread emerged, based partially on an appreciation of the artist’s ability to render face and fabric alike with illusionistic realism, partly on the local penchant for grace in ‘disegno’ and partly as Florence evolved from a Republic to a Medicean Duchy to the use of portraiture as a way to establish immediately recognizable iconic images of the ruling class in all its manifestations: successful businessmen, intellectuals, powerful men and women. Artists like Pinturicchio, Botticelli and Raphael developed this tradition, but it reached its apogee in the crystalline perfection of Bronzino’s exquisitely finished portrayals of the Medici and their supporters.

Fig. 2 Lucian Freud (1922-2011), The Brigadier, 2003-2004 (oil on canvas) / Private Collection / © The Lucian Freud Achive / Bridgeman Images

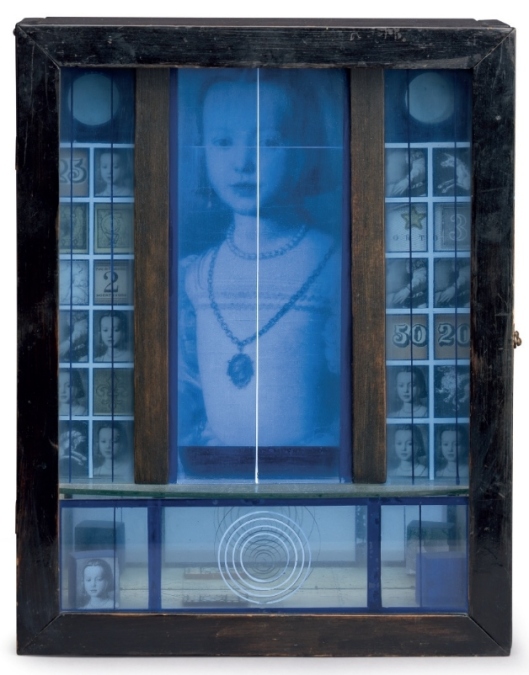

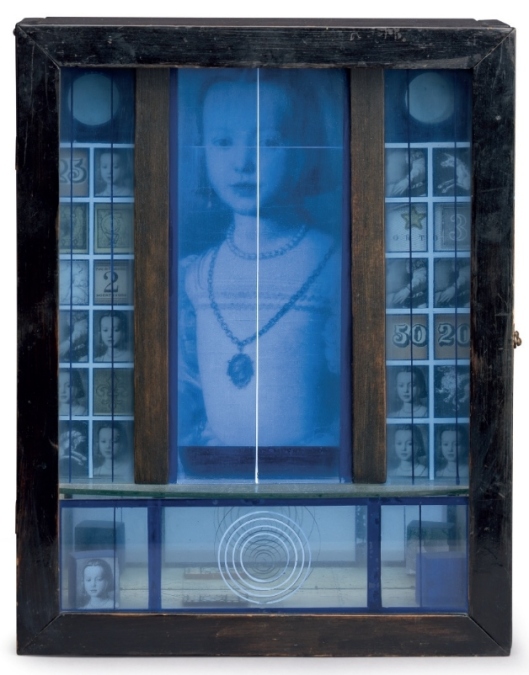

The reverberation of this golden age of portraiture haunts us even today in ways as varied as the original function of the older paintings. A celebrated artist who adapted the conventions and superficial appearance of Renaissance portraiture for her own ends is Cindy Sherman, whose History Portraits (1988-1990) ransack sources as readily identifiable as Raphael’s La Fornarina (Untitled 205) or as generic as Untitled 209, a portrait of a lady in an elaborate 16th-century costume who confronts the viewer with all the haughtiness of a Bronzino aristocrat. Naturally art using photography, or Sherman’s performance art version of it, lends itself to the appropriation of historical images, and with no post-war artist was this accomplished to greater effect than with Joseph Cornell, whose Medici Slot Machines were executed in the 1940s and 50s using printed reproductions of such paintings as the Portrait of Bia de Medici by Bronzino (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence) (fig. 1), which gaze poignantly out at us from behind the glass, part devotional object, part arcade entertainment. In both Sherman and Cornell’s work, one of the preoccupations of the artist is the dialogue with their creative impulses and the history of art. Even if Sherman says “I never did terribly well in art history. I could never memorize the slides”, the History Portraits nevertheless were mainly executed in a studio in Trastevere in Rome and were surely on some level inspired by that environment.

Fig. 1 Joseph Cornell, Medici Princess, Christie’s, New York, 13 May 2014, lot 10, Art © Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

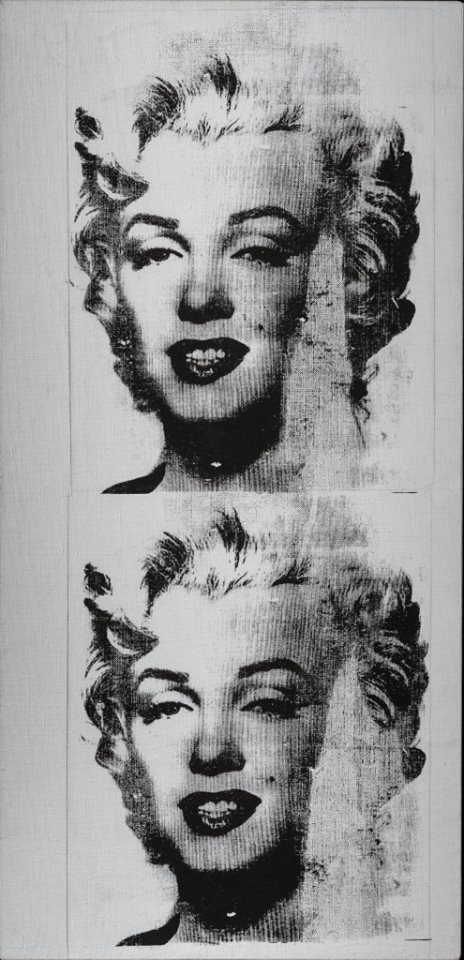

Bronzino’s fascination with power and fashion and his cool, impeccably enameled depiction of the powerful and the beautiful of 16th-century Florence made him a true cultural historian of his time. His portraits immediately conjure up a specific and glamorous moment, his sitters’ detachment rendering them more icon-like than humans with fully realized characterizations. Although there is no evidence of any knowledge of his work, there is a parallel between the portraiture of Bronzino and that of Andy Warhol, the most celebrated purveyor of ‘iconic’ images of the 20th century. Warhol, who became interested in Chairman Mao following Nixon’s visit to China, painted him (fig. 3) in part “since fashion is art now and Chinese is in fashion”. Of course his interest was fired by Mao’s power and celebrity, and his place in the select group of instantly recognizable people, like Jackie O and Liz Taylor, who defined his era and his culture.

Fig. 3 Andy Warhol, Mao, Christie’s, New York, 15 May 2013, lot 39. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

We are grateful to Dr. Carlo Falciani for having furnished the following essay on the picture, translated from the Italian.

The Uffizi Tribuna Gallery, Florence.

This Portrait of a Young Man with a Book is mentioned in 19th-century guides to the Corsini Gallery in Florence, beginning with that of Federigo Fantozzi, who in 1842 listed it as by Andrea del Sarto, an attribution repeated by Giuseppe François in his 1853 guide to the city. Ulderico Medici was the first to ascribe the portrait to Pontormo in his catalogue of the Corsini Gallery of 1886. But apart from these brief references, intended for visitors to the only private art gallery in Florence capable of vying with the famed Medici Collections, the portrait enjoyed little critical acclaim, and art historians only heard of it again recently. All of this is confirmed by the fact that no critics, among the few who studied the work after Gamba in 1921, report having physically seen the painting. They only knew a black and white picture taken by Alinari at the beginning of the 20th century and used in a few ensuing publications. The only explanation for such oblivion is that maybe, some time after 1921, when Bernard Berenson discovered a second version of the painting, the original left the Galleria Corsini and disappeared into other private collections, where it was considered relatively unimportant.

Clapp was the first critic to study the painting. However, he rejected the traditional attribution to Pontormo and, in his 1916 monograph on the artist, it is « ascribed to Pontormo, but neither the colouring, nor the modelling, nor yet the morphology of the figure are his. A copy of this portrait, identical in size, passed from the Lanfranconi Collection, which was sold in Cologne in 1895, into the Sedelmeyer Collection ». In the catalogue entry there is a reference to Alinari picture no. 4198. According to Clapp, the second panel, which was previously in the Lanfranconi Collection, was « a late sixteenth century copy of the portrait erroneously ascribed to Pontormo in the Corsini Collection in Florence ». (Clapp,op. cit., pp. 202-203; for the ex-Lanfranconi painting, see the catalogue of the Dayton Art Institute, Fifty Treasures of The Dayton Art Institute, op. cit., p. 168).

As mentioned above, the Florentine panel was published by Carlo Gamba in 1921 in his brief monograph on Pontormo in Alinari’s Piccola collezione d’arte (illustration n. 45). However, Gamba does not mention the painting in his brief introductory essay, and the attribution is confirmed only by the presence of the picture in the plates; in addition, there are no notes explaining the reasons which led the critic to accept the traditional attribution to Pontormo. In the Alinari picture published by Gamba, we can see that the panel is split right down the middle: the crack, previously reported by Clapp, is clearly visible as it runs from top to bottom through the left cheekbone. This crack, along with certain formal differences, distinguishes this panel beyond all reasonable doubt from that of Lanfranconi version, where the man has a rounder face and the rendering of his eyes is softer.

Jean Alazard discussed the painting in the Corsini Collection in his book Le portrait Florentin de Botticelli à Bronzino, of 1924. He rejected the attribution to Pontormo and highlighted the fact that, in his opinion, the « faiblesse du modèle de la figure et des mains et le coloris disgracieux du visage semblent indiquer une oeuvre d’école » (Alazard, op. cit., p. 177. n. 2). By general consent, the painting was no longer attributed to Pontormo and art history seemed to forget about it until the 1950s, when Carlo Gamba wrote about it again, although he did not publish a new picture of the painting because he preferred the Lanfranconi version, which in the meantime had passed into an American collection. Gamba wrote:

in the Piccola collezione d’Arte I ascribed to Pontormo a portrait in the Corsini Collection generally not accepted as his by art critics. Many scholars say that it is in the tradition of the northern school: they mention different portraits relying on the same stylistic features as examples. Nevertheless, the rendering of the eyes, the mouth and the folds in the clothing are compatible with Jacopo’s style around 1535, and in particular with his style in the beautiful portrait of a young man that passed from Rinuccini to Trivulzio and which can be now admired in the Castello Sforzesco [the reference is to the Portrait of Lorenzo Lenzi, now attributed to Bronzino; fig. 4]. Here too, the uniform greenish background shows how Pontormo’s portraiture had been inspired by models from northern Europe. I reproduce here a second version of it, which is to be found in the Booth Tarkington Collection, Indianapolis. B. Berenson was so kind as to give me the picture of it. We should see the two paintings side by side in order to choose the best version (Gamba, 1956, op. cit., p.16).

Gamba emphatically uses the ‘past’ and ‘conditional’ tenses — ‘I ascribed’, ‘we should see them’ — as though the comparison he yearned to make was no longer possible owing to the fact that one of the paintings was nowhere to be found. (Costamagna, on p. 311 of his monograph on Pontormo, says that the painting under discussion was no longer in the Corsini Collection after the Second World War.) And sure enough, Gamba publishes only the picture of the (formerly Lanfranconi, subsequently) Tarkington panel. In addition, he does not say if the portrait is still to be found in the Corsini Collection; he only says that he published this work in 1921 when it was in the collection. This statement should be intrepreted also in the light of the absence of the painting or any mention of it in subsequent monographs and exhibitions devoted to Pontormo, particularly the exhibition, Pontormo o del primo manierismo fiorentino, curated by Luciano Berti in 1956, where numerous works from Florentine private collections were put on public display, but the Corsini painting was neither exhibited nor mentioned. Nor, indeed, was the painting among those chosen to represent the 16th-century Tuscan school in the famous exhibition held at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence in 1940, Mostra del Cinquecento Toscano. We can only presume once again that the reasons underlying its obscurity are to be found in its fate at the hands of unknown collectors; the painting had lost its appeal and so it was assigned less importance and downgraded to the rank of a work by a member of Pontormo’s workshop. No other study on Pontormo mentions the portrait until the monograph by Philippe Costamagna in 1994. Like Gamba, he admits that he could not see the painting. The only trace we can find of it, and then only as a reminder of its troubled attribution, is in the catalogue of the collection of the Dayton Art Institute, which had acquired the other version of the painting (the Lanfranconi-Tarkington version). The author of the entry rejects the attribution of the Corsini painting to Pontormo, confining himself to reproducing the Alinari picture and the same information as that published by Gamba in 1921 (Fifty Treasures, op. cit., p. 70).

Philippe Costamagna chronicled the many different phases of the painting’s critical history in his study on Pontormo in 1994. He agreed with what Gamba had previously said and, once again, published only the Lanfranconi version as he considered it to be of higher quality than the Corsini painting. However, Costamagna rejected the attribution of both paintings to Pontormo and ascribed the Lanfranconi version to Bronzino, while writing that the Corsini panel is not only lost, but a copy of the Lanfranconi version (Costamagna, op. cit., pp. 310-311). In any event, Costamagna draws attention to the fact that he could not see the two paintings physically because all trace of them had been lost (the Lanfranconi version had entered the Dayton Art Institute in 1949 and had been downgraded in the meantime to the status of a work by an apprentice; it was auctioned by Christie’s on 18 January 1984).

Between 2010 and 2011, I had the opportunity to examine the painting under discussion on fully three separate occasions. I saw it in New York and again while it was being cleaned in a conservation laboratory in Figline Valdarno in December 2010. I also had the good fortune to compare it with other works by Pontormo and Bronzino while I was arranging the exhibition Bronzino. Artist and Poet at the Court of the Medici. This series of coincidences helped me to analyze the painting in some depth. It also led me to draw different conclusions from those of the critics who had only studied the painting in the old photograph, without having had a chance see it.

The painting depicts a young man dressed in black secular garb, sitting at a worktable covered with a green cloth. The fingers of his left hand are leafing through the pages of a hand-written book while he holds a quill in his right hand, his pose appearing to suggest that he has just finished writing. The pages of the book are written in ink as though it were a notebook of some kind, but they are quite unusual: some sentences seem to be crossed out while others appear to have been rewritten, and there are words written crossways on the page as though to suggest a gloss added as an afterthought. In portraits with books, the painter usually depicts printed books or headed writing paper but in this case, since we cannot read the individual words, the book probably hints at his profession: a man of letters or a civil servant versed in the use of coded writing. The short, reddish beard of his young face suggests that he is probably aged between 20 and 30, and even if it is not possible to establish his true identity, we may assume that he is a Florentine intellectual of the same period as the painter who portrayed him, a conjecture suggested both by the friendly tone of his pose and gaze, and by the rapid brushwork. The paintwork, still in perfect condition, was originally applied in a very thin layer with a firm and rapid hand. The only visible sign of deterioration is the vertical crack that caused the panel to divide into two pieces. The crack has been successfully restored by simply repairing the wood and making good the painted surface. The sitter’s eyes are truly alive and the painting is both of exceptionally high quality and, at the same time, surprisingly severe in its reduced palette. The artist’s choices are very clearly in evidence and the style is of such a high standard that the painting cannot be attributed to a mere follower of Pontormo. In fact, it is possible to identify its author with greater certainty.

The first obvious stylistic reference is to Pontormo, as we can see in the structure of the portrait, in the influence of the northern European school and in the ovoid silhouette of the face with the wide-open, sparkling, rounded eyes that are another of the characteristic features of Pontormo’s style. One has but to compare it with the faces in the fresco in Poggio a Caiano or with the tondi painted for the Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicita. The depiction of the soft, tapering hands with their small, oval nails also echoes Pontormo’s style, as does the manner in which the black tunic is rendered, the differences in the grain of the fabric being portrayed with small black-on-black brushstrokes with tiny variations of shade reminiscent of the coat worn by Alessandro de’ Medici in Pontormo’s portrait of him in the John G. Johnson Collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art. The elegantly tapering hands recur in such works as the Visitation in Carmignano, or again in the Philadelphia Portrait of Alessandro de’ Medici, where we can also detect a similar tendency to cause the figure to emerge from an almost monochrome black background, an expedient invented by Leonardo to which Pontormo resorted in many of his works, the most representative of which is the double portrait now in the Fondazione Cini in Venice.

Yet in this Portrait of a Young Man with a Book there are other elements which are unknown in Pontormo’s work and which point us in the direction of his most famous pupil, Agnolo Bronzino, whose style, Giorgio Vasari tells us, was not easy to distinguish from that of Jacopo Pontormo in the years when master and pupil were working together on theEvangelist tondi for the Capponi Chapel in Santa Felicità. Vasari was writing about the years between 1525 and 1528, before Bronzino’s departure for Pesaro in 1530. Sure enough, while it is difficult to tell the two artists’ styles apart in the Capponi Evangelists, Bronzino’s painting tended thereafter to become increasingly polished and compact, the artist focusing increasingly on rendering the tactile evidence of nature as revealed to the senses. The Portrait of Lorenzo Lenzi (fig. 4), a young poet who was a friend and pupil of Benedetto Varchi, is generally dated to shortly before Bronzino’s journey to Pesaro, although it has been attributed to Pontormo in the past, and even Gamba himself, believing it to be by Pontormo, compared it to the portrait under discussion here in 1956. In his Portrait of Lorenzo Lenzi, Bronzino embarks on a style of painting capable of rendering the tactile nature of the tunic’s fabric and a clarity in the modelling of the face, the most direct precedent for which is to be found in this Portrait of a Young Man with a Book.

Fig. 4 Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Lorenzo Lenzi, Castello Sforzesco, Milan.

In this panel too, the face is defined, albeit more rapidly, with a style of painting that imparts solid and luminous volume to it — a feature that most readily distinguishes Bronzino’s painting from that of Pontormo. Also the tapering and supple hands with their soft, wavering, cylindrical fingers, while based on Pontormo’s style, are almost identical with the hands of the sitter in the Portrait of Guidobaldo della Rovere in the Galleria Palatina di Palazzo Pitti in Florence, which Bronzino painted at the end of his stay in Pesaro in 1532 (fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Agnolo Bronzino, Portrait of Guidobaldo della Rovere, Duke of Urbino / Palazzo Pitti, Florence / The Bridgeman Art Library

Yet the comparison with two earlier works by Bronzino is necessary to approach the dating of this portrait. Specific similarities both in the rapid yet soft brushwork and in the way the faces are drawn are also to be found in the Holy Family with St. Elisabeth and the Infant St. John the Baptist of c.1526-1528 in the National Gallery of Art in Washington (fig. 6). In particular, the Infant St. John’s face is painted with the same confidence as we see in this portrait, with the same determination to impart fleshy brilliance to the surface of the eyelids and to the sitter’s lineaments. Also identical are the vibrant, liquid brushstrokes defining the pages of the book — as soft as wax — in this portrait and St. Elisabeth’s lined skin in the Washington Holy Family.

Fig. 6 Agnolo Bronzino, The Holy Family, Samuel H. Kress Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Further comparisons may be made with the Lamentation over the Dead Christ in the Uffizi (fig. 7), which Bronzino painted around 1529, where the Magdalene’s oval face has the same polished surface over which the light flows with intense clarity, defining the purity and fullness of her cheeks and eyes.

Fig. 6 Agnolo Bronzino, The Dead Christ with the Virgin and St. Mary Magdalene / Galleria degli Uffzi, Florence / The Bridgeman Art Library

In conclusion, all of the above features come together to suggest the attribution of this outstanding portrait, which has finally come to light again after decades of oblivion, to take up its rightful place at the heart of the study of Florentine 16th-century painting, to the hand of Agnolo Bronzino, who must have painted it in strict adherence to Pontormo’s style between 1525 and 1527.

Carlo Falciani, Firenze, 20 Maggio, 2012

Christie’s. RENAISSANCE, 28 January 2015, New York, Rockefeller Plaza