Étiquettes

Angelo Marani, Cocktail Dress, Cocktail Dress and Stole, Cocktail ensemble, Emanuel Ungaro, Evening Dress, Evening ensemble, fall/winter 1968-1969, fall/winter 1974–75, fall/winter 1981-1982, fall/winter 1987-1988, fall/winter 1988-1989, fall/winter 1989–90, fall/winter 1997-1998, fall/winter 1999-2000, fall/winter 2000–01, fall/winter 2003–2004, fall/winter 2005-2006, Fausto Sarli, Givenchy by Alexander McQueen, Jean-Louis Scherrer, Krizia, Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, Milwaukee Art Museum, Pierre Balmain, Silk moiré taffeta and satin, Ted Lapidus, Tilmann Grawe, Valentino

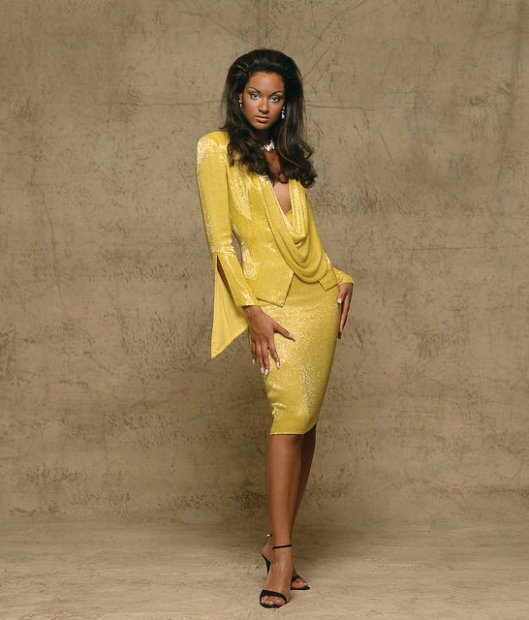

Tilmann Grawe (French) Cocktail Dress, fall/winter 2003–2004 Silk moiré taffeta and satin © International Art & Artists

MILWAUKEE, WIS.- The Milwaukee Art Museum brings haute couture to the city in Inspiring Beauty: 50 Years of Ebony Fashion Fair. Open now through May 3, it is a story of vision, innovation and power told through the prism of iconic fashion from Oscar de la Renta, Givenchy, Valentino, Dior, Pierre Cardin, Yves Saint-Laurent, Patrick Kelly and Emanuel Ungaro, among others.

Krizia (Italian) Cocktail ensemble, fall/winter 1981-1982. Silk taffeta and satin © International Art & Artists

“The Museum is thrilled to showcase its debut fashion exhibition and partner with International Arts & Artists to feature Inspiring Beauty,” said Daniel Keegan, director of the Milwaukee Art Museum. “This is a stunning exhibition that will be dramatically installed to give the visitor a true runway experience.”

Ted Lapidus (French) 2 of 2 coordinating cocktail dresses (white), fall/winter 2000–01. Hand-painted silk faille, glass beads, plastic sequins, leather, cotton embroidery thread Lent by Johnson, LLC Chicago History Museum, Johnson Publishing.

Inspiring Beauty is presented in three sections that explore the three major themes of the exhibition. The first section of the exhibition, Vision, explores Eunice Johnson’s role as the creative force behind the Ebony Fashion Fair. It features costumes that reflect power, affluence and influence, expressing some of the traveling show’s recurring aesthetic ideas.

Angelo Marani (Italian) Cocktail Ensemble, fall/winter 2005-2006. Fox, rabbit, mink, synthetic lace and ribbon, leather, nylon/viscose/cotton blend denim © International Art & Artists

The second section of the exhibition, Innovation, looks at the boldness and experimentation of Johnson Publishing Company. Garments in this section reflect the full breadth of fashion fantasy that the traveling show brought audiences while the film highlights the historic significance of Johnson company publications.

Fausto Sarli (Italian) Cocktail Ensemble, fall/winter 1999-2000. Silk chiffon and glass beads © International Art & Artists

The final section, Power, features Inspiring Beauty’s most elaborate, luxurious and dramatic ensembles. Costumes by Valentino, Bob Mackie, Henry Jackson and Alexander McQueen reflect the glamour and showmanship that created the dynamic visual experience that audiences expected.

Jean-Louis Scherrer (French) Cocktail ensemble, fall/winter 1989–90. Silk and metallic thread jacquard, glass beads and rhinestones, metallic fringe, plastic sequins. Lent by Johnson Publishing Company, LLC Johnson Publishing

“At the heart of this dynamic exhibition are the stunning gowns, feathered coats, and statement designs seen in the seventy-plus ensembles by designers including Valentino, Givenchy, Oscar de la Renta, Bob Mackie, Missoni, Patrick Kelly, Alexander McQueen, Christian Dior, Vivienne Westwood, and more, all selected from a collection of thousands that Mrs. Johnson amassed in five decades,” said Keegan.

Jean-Louis Scherrer (French), Cocktail Ensemble, fall/winter 2000-2001. Fox, goat, mink, Persian lamb, leather © International Art & Artists

To celebrate Milwaukee’s local connection to the Ebony Fashion Fair, a section of the exhibition will include thirteen designer garments from Mount Mary University’s signature Ebony Fashion Fair collection, part of the its 10,000 piece Historic Costume Collection. Mount Mary’s selections will feature garments by Koos Van Den Akker, Vivienne Westwood, Thierry Mugler, and Anna Sui, among others.

Emanuel Ungaro (French), Evening Dress, fall/winter 1987-1988. Silk satin and taffeta © International Art & Artists

The Ebony Fashion Fair circuit included 170 stops each year, including Milwaukee. In addition to appearing at the now-defunct Garfield Theater on the city’s north side, Mount Mary University presented the Ebony Fashion Fair to sold-out audiences in its Kostka Theater on several occasions.

Emanuel Ungaro (French), Bridal Gown, fall/winter 1996-1997. Cotton/synthetic blend lace, embroidered silk, plastic ‘pearl’ beads and sequins, glass beads © International Art & Artists

Inspiring Beauty: 50 Years of Ebony Fashion Fair was developed by the Chicago History Museum in cooperation with Johnson Publishing Company, LLC, presented by the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum, and toured by International Arts & Artists, Washington, DC. It is presented at the Milwaukee Art Museum by Mount Mary University, and supported by Harley-Davidson Motor Company, the Joseph R. Pabst Fund of the Greater Milwaukee Foundation, the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Friends of Art, Angela and Virgis Colbert, Potawatomi Hotel & Casino, Milwaukee (WI) Chapter The Links, Incorporated, and the Milwaukee Art Museum’s African American Art Alliance. Inspiring Beauty: 50 Years of Ebony Fashion Fair is co-organized at the Museum by Camille Morgan, Exhibitions Curatorial Coordinator at Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, University of Chicago and Monica Obniski, Demmer Curator of 20th and 21st Century Design at the Milwaukee Art Museum. It will be on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum February 5 through May 3, 2015.

Valentino (Italian) Evening ensemble, fall/winter 1974–75. Silk chiffon, ostrich feathers Lent by Johnson Publishing Company, LLC Chicago History Museum, Johnson Publishing

Pierre Balmain (French) Cocktail Dress and Stole, fall/winter 1988-1989. Silk chiffon © International Art & Artists

Pierre Balmain (French) Cocktail Dress and Stole, fall/winter 1988-1989. Silk chiffon © International Art & Artists

Marc Bohan (French) for Christian Dior, Evening Ensemble, fall/winter 1968-1969. Wool, plastic sequins, glass and plastic beads, metallic thread © International Art & Artists

Givenchy (French) by Alexander McQueen, Evening Ensemble, fall/winter 1997-1998. Synthetic raffia mounted on silk gauze © International Art & Artists