Gerhard Richter (b. 1932), Vierwaldstätter See (Lake Lucerne) detail. Oil on canvas, 120 x 150 cm Executed in 1969 Estimate on Request © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

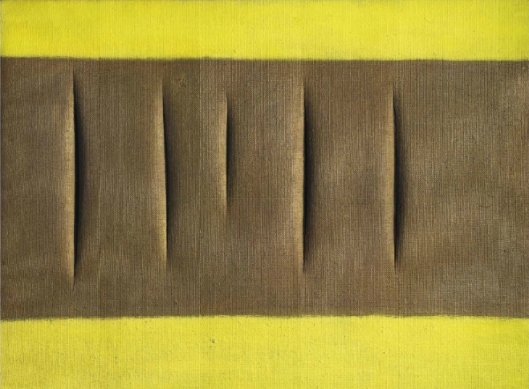

LONDON.- In February 2015, Christie’s will offer another outstanding week of auctions led by Gerhard Richter’s Vierwaldstätter See (Lake Lucerne), 1969, a sublime photo-painting of the famous Swiss Lake, held in the same private collection since 1973, which is presented during the Evening Auction in London on 11 February. Following the world record price of $69.6million achieved for Cy Twombly’s Untitled in November, the Evening Auction also includes Untitled (New York City), 1970, a mesmerising large-scale work from the same seminal series of ‘blackboard’ paintings. The week will also feature a selection of art donated by former students of Goldsmiths, University of London to benefit the building of a new gallery to be offered during our Day sale on 12 February.

Second highest pre-sale low estimate in Europe

This season offers the second highest, pre-sale low estimate for any Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Auction ever to take place in Europe at £95million (64 lots). The record Post War and Contemporary Art Evening auction in Europe was held by Christie’s in June 2012, and realised £132 million against a low pre-sale estimate of £102 million. Last year’s equivalent February season at Christies broke the record for any Post War and Contemporary Art week in Europe when it realised £176 million, including the benchmark sale of Arte Povera and Post-War Italian art, Eyes Wide Open: an Italian Vision, which realised a total of £38million.

GERHARD RICHTER’S SWISS LAKE

The Post-War and Contemporary Evening Auction is led by Gerhard Richter’s Vierwaldstätter See (Lake Lucerne) (estimate on request). The painting is the largest of a distinct series of four views of the famous Swiss lake painted by Richter in 1969. Purchased from the artist by the present owner in 1973 after its inclusion in the Grand Art Exhibition at the Haus der Kunst Munich, it stems from a landmark period in Richter’s early oeuvre. Three further works by Gerhard Richter are also included in the auction spanning three decades of his celebrated practice: Karmin (Carmine), 1994 (estimate: £9,000,000 – 14,000,000), Abstraktes Bild, 1986 (estimate: £1,000,000 – 1,500,000), Abstraktes Bild, 1990 (estimate: £3,500,000 – 4,500,000).

Gerhard Richter (B. 1932), Vierwaldstätter See (Lake Lucerne), signed, numbered and dated ‘226/2 Richter 69’ (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 47¼ x 59¼in. (120 x 150cm.). Painted in 1969. Estimate Upon Request. © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: The Artist.

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 1973.

Property from a Distinguished European Collection

Literature: XXXVI Biennale Internationale dell’Arte, German Pavilion, exh. cat., Venice 1972, p. 41 ( incorrectly referenced as no. 226-1; illustrated, p. 68).

J. Harten (ed.) and D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: Bilder 1962-1985, exh. cat., Dusseldorf, Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1986, p. 374 (incorrectly referenced as no. 226-1; illustrated, p. 102).

Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (ed.), Gerhard Richter, Werkübersicht/Catalogue Raisonné: 1962-1993, vol. III, Ostfildern-Ruit 1993, p. 158 (incorrectly referenced as no. 226-1; illustrated, unpaged).

H. Friedel (ed.), Gerhard Richter: Atlas, Cologne 2006, p. 853.

D. Elger (ed.), Gerhard Richter. Landschaften, Ostfildern-Ruit 2011, p. 174 (incorrectly referenced as no. 226-1; illustrated in colour, p. 40).

Exhibited: Munich, Haus der Kunst, Große Kunst Ausstellung, Landschaft. Figur und Objekt in der Landschaft, 1973, no. 884 (illustrated, p. 290).

This work will be included in the forthcoming 2nd volume of the Gerhard Richter. Catalogue raisonné, edited by Dietmar Elger, under cat. no. 226-2.

Notes: ‘Just because landscape is beautiful. It’s probably the most terrific thing there is… I felt like painting something beautiful’ (Richter, Interview with Rolf Gunther Dienst, 1970, quoted in Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of Painting. Writings and Interviews 1962-1993, ed. Hans-Ulrich Obrist, trans. David Britt, London, 1995, pp.63-64).

‘Of course, my landscapes are not only beautiful or nostalgic, with a Romantic or classical suggestion of lost Paradises, but above all “untruthful” (even if I did not always find a way of showing it); and by “untruthful” I mean the glorifying way we look at Nature – Nature, which in all its forms is always against us, because it knows no meaning, no pity, no sympathy, because it knows nothing and is absolutely mindless: the total antithesis of ourselves, absolutely inhuman. Every beauty that we see in landscape – every enchanting colour effect, or tranquil scene, or powerful atmosphere, every gentle linearity or magnificent spatial depth or whatever is a our projection; and we can switch it off at a moment’s notice’’ (G. Richter, 1986, quoted in H.-U. Obrist (ed.), Gerhard Richter: The Daily Practice of Painting. Writings and Interviews 1962-1993, trans. D. Britt, London, 1995, p. 124).

‘A painting by Caspar David Friedrich is not a thing of the past. What is past is only the set of circumstances that allowed it to be painted: specific ideologies, for example. Beyond that, if it is any “good”, it concerns us – transcending ideology – as art that we consider worth the trouble of defending (perceiving, showing, making). It is therefore quite possible to paint like Caspar David Friedrich today’ G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger (ed.), Gerhard Richter Landscapes, exh. cat., Sprengel Museum Hannover, 1998, p. 12).

‘Their significance lies, not in a critical mass but in the prominent position they occupy in the artist’s oeuvre, and in how he thrusts them into dialog with the other work. In several scenes- conceptual, aesthetic, and technical- they would serve as a bridge from the photo-paintings to the abstract paintings soon to come’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 173).

‘I don’t mistrust reality of which I know next to nothing. I mistrust our model of reality conveyed to us by our senses, which is imperfect and circumscribed’ G. Richter in an interview with Rolf Schön, 1972, reprinted in: H.-U. Obrist (ed.), Gerhard Richter. The Daily Practice of Painting, London 1995, p.73).

A sublime vista at the confluence of two headlands in the middle of Lake Lucerne, Vierwaldstätter See is the largest of a distinct series of four views of the lake painted by Richter in 1969. Purchased by the present owner in 1973 from the artist after the work was included in the Grand Art Exhibition held in the Haus der Kunst Munich, the work represents a landmark period in Richter’s oeuvre. During the early to mid 1960s Richter had made his name with his black and white photo-paintings, which fell under the early aegis of German Pop Art, but it was in the years between 1967-1970 that the full expanse of his vision would be unveiled in an unprecedented period of creativity in which all forms of style in painting from Abstract to Figurative, Minimalist to Constructive were explored and amalgamated with equal technical virtuosity and aplomb. Balancing the composition on the knife-edge between figuration and abstraction,Vierwaldstätter See in many ways prefigures the seminal series of seascapes completed in 1969-70, and the two series together can be seen to represent the concepts which run throughout his oeuvre to today. Faced with the panorama, the viewer’s eye is carried along the passage of softened, almost smoky clouds, around the darkened headland onto a distant and illusive horizon, at once inviting the viewer into the landscape whilst at the same time rendering a view that is entirely unobtainable. As Robert Storr states ‘the viewer is thus left in a state of perpetual limbo bracketed by exigent pleasures and an understated but unshakable nihilism. Those who approach Richter’s landscapes with a yearning for the exotic or the pastoral are greeted by images that first intensify that desire and then deflect it’ (R. Storr (ed.),Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, pp. 65-66). Meticulously painted, with feathered brushstrokes deliberately visible as evidence of Richter’s process, Vierwaldstätter See acts as a precursor to the sweep of the squeegee which would later define his abstract works. Emerging through the delicate brushstrokes, layers of midnight blue deepen Richter’s grisaille palette and create an intense surface that radiates with enduring natural beauty.

One of the largest lakes in Switzerland, Lake Lucerne has an elusive set of contours that has continued to inspire painters through the ages most notably J.M.W. Turner paintings of the Rigi. For this painting Richter appears to have chosen a view from Vitznau, through the narrow strait at the centre of the lake, between the two rocky promontories called respectively Untere and Obere Nase. Within this apparently photo-real view Richter has conjured an extraordinary atmosphere that dissolves in and out of focus with an ambient haze that creates an almost ethereal environment, recognisably Lake Lucerne yet eluding any exact detail or location. Frequently returning to Switzerland throughout his life, Richter’s landscape is a poetic representation of a well-loved destination. Playing with the conventions of the romantic sublime, Richter in Vierwaldstätter See simultaneously and emphatically refutes the historicized associations of landscape painting, redefining humanity’s role within, and in relation to, nature.

1960S – REVOLUTIONARY YEARS

Painted in 1969, Vierwaldstätter See emerges from a deeply creative moment in the artist’s career and it was in this year that the sheer multiplicity of Richter’s practice became apparent to the public. In his first solo show in a public institution at the Gegenverkehr e.V. in Aachen in 1969, Richter displayed his new forays into abstraction alongside landscape and figurative works based on photographic sources. Included in this show were early photo paintings such as Falbarer Trockner (Folding Dryer) (1962), colour charts such as 192 Farben (192 colours) 1966 and abstracted townscapes such as Stadtbild Paris 1968. Deliberately hung without any sense of chronology or theme, in many respects mirroring his own indifference to the conventional matters of style and subject, this show demonstrated the multiplicity of Richter’s practice in these fertile years.

In 1969, Richter moved away from the straightforward photo paintings of his earlier years. Developing the way in which he initially obfuscated the photographic image, by 1969 Richter demonstrated a far more nuanced and skillful approach to his continued investigation of representation, figuration and abstraction. As part of this process Richter embarked on an experimental series of landscapes. Varying in scenery and painting techniques, the first were loose painterly explorations of aerial photographs of cities and townscapes and later, mountain landscapes and park scenes with their hard-edge textured paint surfaces. In the months leading up to the creation of Vierwaldstätter See Richter produced a series of Swiss Alpine landscapes. With their crisp detail these works are a radical counterpoint to his later interpretations of the alpine landscape visible in Vierwaldstätter See. In this respect Vierwaldstätter See with its more mature, almost luxurious surface, can be seen to resonate more closely with his romanticized, nearly abstract, seascapes that Richter went on to paint towards the end of 1969 and through to 1970.

THE LANDSCAPE EMBODIED IN A BRUSHSTROKE

The artist’s facility with his medium and his technical skill mark the Vierwaldstätter See series and the seascapes of this period as some of his most accomplished and conceptually innovative. The rich, almost velvet surface ofVierwaldstätter See and depth it provides to the composition, shows the development in Richter’s style away from the German pop photo paintings of the early 1960s. This technical ability meant that at the same time as evoking German Romanticism, Richter managed to create paintings that were entirely radical, standing as subtle and subversive responses to tradition. Vierwaldstätter See appears to have been brilliantly captured in movement, the artist visualising the image as if from the window of a passing car or airplane. The sense of transience, of a view captured in a fleeting moment, reiterates our own alienation from nature.

In carrying out the composition, Richter has manipulated the surface of the paint by dragging a dry brush across the canvas while the paint is still wet. This ultra-fne horizontal brushwork creates a hypnotic effect which becomes more apparent as you approach the canvas, with each individual brushstroke becoming visible as an individual element of a coherent whole. Stepping back from the work allows these elements to melt away revealing the softened edges of the lake’s surface. The edges are blurred to the point of abstraction such that the waterline and the dramatic mountainous shore blur in the delicate featherlike brushstrokes and subtle chromatic variation. Richter’s emphatic focus on the brushstroke renders a complex, almost luxurious surface. Areas of gloss mark the physical surface of the lake’s shoreline which has so often inspired painters throughout history.

Richter’s unique painting method strengthens the tension and ambivalence between painting and photography, abstraction and reality. The photographic source is skillfully recreated whilst at the same time brushstrokes marks remain visible, posing a constant question of the viewer as to the nature of the image they are faced with. The subtle blurring of the image is a deliberate strategy in Richter’s photo paintings as a means of creating distance between the viewer and the representation of nature, emphasizing that neither painting, nor photography, can bridge the gap between reality and experience.

THE ROMANTIC SUBLIME

For Richter, his early landscapes represented a determined departure from the politicized painting and the avant-gardism of the late 1960s. As he explained, ‘just because landscape is beautiful, it’s probably the most terrific thing there is…I felt like painting something beautiful’ (G. Richter quoted in R. Storr (ed.), Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, pp. 65-66). In this departure from the contemporary tides in painting, Richter was engaging with the legacy of eighteenth and nineteenth century German Romanticism and asserting his right to create art that addressed any subject matter or artistic tradition. Through this assertion works like Vierwaldstätter See demonstrate the artist’s continued efforts to salvage painting as a medium, skillfully depicting the sublime through delicate layers of paint. The subtle fusion between the painted image and the reality of the landscape ultimately mean that Richter’s landscape paintings possess the same conceptual nuances that unite much of the artist’s oeuvre.

We can particularly see the affinity between Vierwaldstätter See and the dramatic mountain landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, and rightly a comparison is frequently made between the two artists. As Elger notes, when Richter was still an art student in the GDR, he used to travel to Dahlem to visit the museums and always took time to view the paintings by Friedrich. Richter has himself commented on this legacy, affirming the German romantic influence. As the artist explained, ‘a painting by Caspar David Friedrich is not a thing of the past. What is past is only the set of circumstances that allowed it to be painted: specific ideologies, for example. Beyond that, if it is any “good”, it concerns us – transcending ideology – as art that we consider worth the trouble of defending (perceiving, showing, making). It is therefore quite possible to paint like Caspar David Friedrich today’ (G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger (ed.), Gerhard Richter Landscapes, exh. cat., Sprengel Museum Hannover, 1998, p. 12).

Nevertheless, while Richter was clearly channeling the visual language of Friedrich’s paintings, his intentions were far more complex and subversive. Vierwaldstätter See is deliberately imbued with the Romantic connection through its sense of distance and expanse, yet with one key difference. Whereas Romantic paintings often meet the viewer halfway, usually by means of a surrogate figure in the landscape such as the turned figure in The Monk by the Sea, Richter’s landscapes in contrast remain uninhabited. In this way Richter dramatically redefines the historicized understanding of humanity’s role in nature. In Vierwaldstätter See Richter invites the viewer to gaze upon the unmediated beauty of the sublime landscape without ever making contact, remaining forever frustrated by its intangibility.

For Richter, all nature is fundamentally outside the human purview and beyond any religious claims. As Richter has said of his landscapes, ‘[they] are not only beautiful or nostalgic, with a Romantic or classical suggestion of lost Paradises, but above all ‘untruthful’… and by “untruthful” I mean the glorifying way we look at Nature – Nature, which in all its forms is always against us because it knows no meaning, no pity, no sympathy, because it knows nothing and is absolutely inhuman’. (G. Richter, quoted in J. Nestegrad (ed.), Gerhard Richter: The Art of the Impossible – Paintings 1964-1998, Oslo 1999). By this means Richter used his landscape paintings as ‘visual models of a lost truth’ and thus they can be seen directly to complement his abstract works which he has described as ‘fictive models’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter Landscapes, exh cat., Sprengel Museum, Hannover, 1998, p. 21). Richter himself has stated ‘For me there is no difference between a landscape and an abstract painting. In my opinion the term “realism” makes no sense’ (G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 273).

LAKE LUCERNE

In his efforts to salvage painting, examining the way in which it had become seemingly obsolete in the age of the photograph, it is of no coincidence that Richter was drawn to the vivid landscapes of the great Swiss lakes, in particular Lake Lucerne. The dramatic, awe inspiring mountains, combined with the lake’s placid surface gave rise to an inspirational moment for many artists, including Alexandre Calame, Albert Bierstadt, John Ruskin and most notably J.M.W. Turner. For Turner, the Swiss lakes inspired a series of works which embody the tradition of the romantic sublime. Like many artists before him, Turner initially headed south in search of light and in 1819 travelled to Italy, later visiting Switzerland in the 1840s where he was captivated by the sublime beauty of the mountain landscape. In many ways this can be seen to resonate with Richter’s own travels in 1969, beginning further south in Corsica where the study of light dominates his works, and then later to Switzerland where he seems to have encountered the same sense of awe and sublime as Turner did over a century before him.

ATLAS: THROUGH THE ARTIST’S LENS

It was also in 1969 that Richter first began to compile his photographic source material, known now as Atlas that would soon become a referential touchstone throughout his career. This ever-growing subjective anthology of photos, some found by and others taken by Richter, was first exhibited in 1970 under the title Studies 1965-1970 at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, and later would be formally exhibited under the Atlas title in 1972 in Utrecht. Since these early years Richter has added to and exhibited this shifting, swelling flow of source material, such that it stands as a fascinating counterpoint to his paintings.

Although Richter only began to compile Atlas in 1969, his use of photographs as his source material began in 1962 when no longer satisfied with his earlier abstract work he turned to paintings based on found photographs. In doing so, Richter was looking for a new means of painting, ‘free from “literary effect”, historical bias and the decorum of traditional composition’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 49). Appearing initially as a European response to the American Pop Art movement, the artist began by mining images from newspapers, books and other published materials, rendering them in cool, painted monochrome. Richter surmised that working from a photo in this way was the perfect means of escape: ‘a photograph – unless the art photographers have ‘fashioned’ it is simply the best picture I can imagine… it is a perfect; it does not change; it is absolute, and therefore autonomous and unconditional… This is something that just has to be incorporated into painting’ (G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger,Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 49). It was not until 1968 that Richter began to use his own photographs, collecting colour pictures of his first holiday abroad with his family to Corsica.

Building on these earlier photopaintings, Richter’s first colour investigations of the natural landscape began in 1968, just one year before he created Vierwaldstätter See. Buoyed by his recent exhibition success, his recent appointment to professorship at Hamburg Art Academy and birth of his daughter Betty, Richter travelled to Corsica on his first real family vacation. Armed with his camera, he captured numerous rolls of film, which he later translated into paintings. These works contain the same wide, open horizon trailing into the distance and low, dramatic sky as is captured inVierwaldstätter See, simultaneously invoking and puncturing both abstraction and also Romanticism.

REALITY AND REPRESENTATION

Vierwaldstätter See is a masterful rendition of a Swiss alpine vista that vibrates with references to the Romantic tradition so beloved in Germany. Low clouds nestle between brooding headlands in a dramatic swirl of grey and midnight blue, with a hazy sense of the vast distance in the horizon which intentionally raises the romantic notion of the sublime. It is a masterful study of light and landscape, tone and form. Delicate feathered brushstrokes evoking a photographic source, create an intense illusion of reality, but one that is distant and elusive, that nature can never fulfill. Executed at the end of the 1960s, Vierwaldstätter See comes from an intensely creative moment in Richter’s career when he was investigating for the first time the unities between abstract and figurative painting. As the artist once said, ‘if the Abstract paintings show my reality, then the landscapes and still-lives show my yearning… though these pictures are motivated by the dream of classical order and a pristine world – by nostalgia in other words – the anachronism in them takes on a subversive and contemporary quality’ (G. Richter, quoted in A. Zweite (ed.), Gerhard Richter: Catalogue Raisonné 1993-2004, Dusseldorf 2005, p. 33).

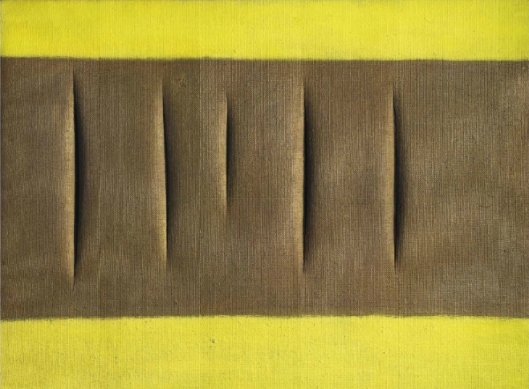

Gerhard Richter (b. 1932), Karmin (Carmine), signed, numbered and dated ‘Richter 1994 810-1’ (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 78¾ x 78¾in. (200 x 200cm.).Painted in 1994. Estimate £9,000,000 – £14,000,000 ($13,617,000 – $21,182,000). © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London.

Lord Anthony Jacobs, London.

Gagosian Gallery, London.

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 2010.

Property from a Distinguished European Collection

Literature: Gerhard Richter 1998, exh. cat., London, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, 1998, no. 810-1 (illustrated in colour, p. 89).

Gerhard Richter Werkverzeichnis 1993-2004, exh. cat., Dusseldorf, K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2005, p. 309, no. 810-1 (illustrated in colour, p. 271).

Exhibited: London, Anthony d’ Offay Gallery, Gerhard Richter: Painting in the Nineties, 1995, no. 19 (illustrated in colour, pp. 53 and 84).

Notes: ‘Almost all the abstract paintings show scenarios, surroundings and landscapes that don’t exist, but they create the impression that they could exist. As though they were photographs of scenarios and regions that had never yet been seen’ (G. Richter, quoted in ‘I Have Nothing to Say and I’m Saying It: Conversation between Gerhard Richter and Nicholas Serota ‘, in Gerhard Richter: Panorama, exh. cat., London, 2011, p. 19).

‘Richter has taken to faying the painted skin of his canvases with a spatula in broad strokes or long, wavering stripes leaving behind abraded, shimmering surfaces that at their sheerest and most luminous look like the Aurora Borealis suspended above various red, orange, yellow, green, blue or violet planets’ (R. Storr, Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, p. 81).

‘Abstract paintings are fictitious models because they visualize a reality, which we can neither see nor describe, but which we may nevertheless conclude exists. We attach negative names to this reality; the un-known, the un-graspable, the infinite, and for thousands of years we have depicted it in terms of substitute images live heaven and hell, gods and devils. With abstract painting we create a better means of approaching what can be neither seen nor understood’ (G. Richter, quoted in R. Nasgaard, ‘Gerhard Richter’, Gerhard Richter: Paintings, exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1988, p. 107).

‘[In this period] Richter attempted to take possession of his domestic happiness through a long and painterly process, as if only this would make the situation believable’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 327).

Enshrouded in a luxurious velvety Carmine red veil, Karmin (Carmine) engulfs the viewer in its mysterious crimson glow. Like a luscious velvet curtain draped over a window, or rich cloth that cascades over the contours of a figure, this majestic painting tempts the viewer into its warm hearth with its enigmatic surface. In Karmin, Richter has become captivated by the rhythmic application and removal of paint in horizontal and vertical planes, each successive stroke of the squeegee drawing a veil across the previous layer of paint like a curtain, playing with the notion of presence and absence. Through addition and subtraction to the point of harmony, palimpsests of emerald green and azure blue emerge and dissolve through the apertures in the surface, offering glimpses of an imaginary landscape somewhere in the distance. Created in 1994, the painting reflects the supreme contentment of the artist. In 1991 Richter held his breakthrough exhibition at Tate Gallery, London and in 1993 he received a major touring retrospective Gerhard Richter: Malerei 1962-1993 curated by Kasper König accompanied by a three volume catalogue raisonné edited by Benjamin Buchloch. This latter exhibition containing 130 works carried out over the course of thirty years, was to entirely reinvent Richter’s career. As critic Doris von Drathen wrote shortly after, ‘there are exhibitions that, like great milestones, reset the standards in contemporary art. Richter’s retrospective, launching now at the ARC in Paris, is of this quality’ (D. von Drathen quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 323). The beauty and balance of Karmin can be understood as a reflection of this personal satisfaction. Indeed a sense of his enriched emotional life is evident in the confident gestures, radiance and majestic palette of the painting. In 1994, whilst he was completing Karmin, Richter was also engaged in a series of paintings depicting his new wife Sabine Moritz. In particular the photorealist masterpiece, Lesende demonstrates a beautiful tenderness towards its subject, light illuminating Sabine’s elegant profile. The following year, Richter was to begin a suite of paintings entitled S. mit Kind, now housed in Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Depicting Sabine cradling their young son Moritz in her arms, Richter has again removed vertical swathes of paint with the squeegee to in effect reveal the fgures from behind the front surface. As Dietmar Elger suggests, in this period ‘Richter attempted to take possession of his domestic happiness through a long and painterly process, as if only this would make the situation believable’ (G. Richter quoted in D. Elger,Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 327). It was in 1995 that Karmin was exhibited for the frst time in Gerhard Richter: Painting in the Nineties at Anthony d’Offay Gallery; an acclaimed show including works that now reside in major museum collections such as Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Tate Modern, London, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, La Caixa Foundation, Barcelona and The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

Executed during the run of the touring retrospective described above, this intersection of horizontal and vertical strokes in a grid-like assembly, and the harmonious intermarriage of weton- wet oil paint, creates a near sublime effect that recalls Richter’s greatest cycle of abstracts, the Bach series (1992, Moderna Museet, Stockholm) which were premiered here for the first time. As Richter has described, In Karmin vast antecedent layers laid down in horizontal swathes are revealed and submerged in the artist’s subsequent painting. Through the horizontal strokes of paint, Richter has swept through the lustrous medium in vertical planes from top to bottom, in an act of creative destruction, partially obscuring and at the same time allowing jewel-like blues and greens to interact with velveteen reds at the centre of the composition. As Robert Storr has observed, ‘Richter has taken to faying the painted skin of his canvases with a spatula in broad strokes or long, wavering stripes leaving behind abraded, shimmering surfaces that at their sheerest and most luminous look like the Aurora Borealis suspended above various red, orange, yellow, green, blue or violet planets’ (R. Storr, Gerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, p. 81).

In Karmin, Richter creates a work that celebrates the sensual pleasures of freely applied paint and colour, just as he accomplished in the Bach series. In addition to the rich optical experience of the painting, Richter encourages the viewer to immerse him or herself in the imaginary space of the composition. He insists that ‘paintings are always illusionistic’ so that a line, form or colour ‘is only interesting when it releases an interesting association’ (G. Richter quoted in R. Nasgaard, ‘Gerhard Richter’, Gerhard Richter: Paintings, exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 1988, p. 107). In Karmin the cumulative layers of non-representational paint in hues of red, green and blue, cannot help but evoke the English rose garden or a Mediterranean sunset, offering a romantic window onto the world. Just as Claude Monet had done generations before him in his Nymphéas, Richter beautifully illuminates the shifting boundary between figuration and abstraction. Whilst Monet’s immersive, shimmering images of waterlilies and reflections on the quicksilver water of the pond at Giverny pushed figuration to the brink of abstraction, emphasising the illusory aspect of the lush, textured paint itself, in Karmin Richter has arrived at the same effect through different means.

For Richter, his free abstraction is the product of a long investigation into the possibilities of painting spanning more than five decades. Coming full-circle from his early Tisch (1962) in which he cancelled his photorealist image with haptic swirls of grey paint, Richter began in the 1980s to freely overlay his canvases with colourful streaks and drags of pigment using his signature squeegee. As Dietmar Elger has observed, ‘for Richter, the squeegee is the most important implement for integrating coincidence into his art. For years, he used it sparingly, but he came to appreciate how the structure of paint applied with a squeegee can never be completely controlled. It thus introduces a moment of surprise that often enables him to extricate himself from a creative dead-end, destroying a prior, unsatisfactory effort and opening the door to a fresh start’ (G. Richter quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 251). This method was to find its purest articulation between 1989 and 1994 with large-format paintings such asKarmin. Deconstructing the relationship between figure and ground, Richter was embracing the contingency of his medium, enjoying the effects of the spontaneous yet confident application of paint. As he once explained, ‘it is a good technique for switching off thinking consciously, I can’t calculate the result. But subconsciously, I can sense it. This is a nice ‘between’ state’ (G. Richter quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 251).

In his most definitive elucidation of his abstract method published in the Documenta 7 exhibition catalogue in 1979, Richter explained that for him, the abstract painting is no less a representation of reality than those photorealist figurative paintings of landscapes, people or places. Rather it represents the other end of the same spectrum, depicting the unseen, unspoken, intangible reality. As he elaborated, ‘every time we describe an event, add up a column of figures or take a photograph of a tree, we create a model; without models we would know nothing about reality and would be like animals. Abstract paintings are fictitious models because they visualize a reality, which we can neither see nor describe, but which may nevertheless conclude exists. We attach negative names to this reality; the un-known, the un-graspable, the infinite, and for thousands of years we have depicted it in terms of substitute images live heaven and hell, gods and devils. With abstract painting we create a better means of approaching what can be neither seen nor understood’ (G. Richter quoted in R. Nasgaard, ‘Gerhard Richter’, Gerhard Richter: Paintings, exh. cat., Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 1988, p. 107).

Gerhard Richter (b. 1932), Abstraktes Bild, signed, numbered and dated ‘Richter 1990, 720-3’ (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 48¼ x 40¼in. (122.5 x 102.3cm.). Painted in 1990. Estimate £3,500,000 – £4,500,000 ($5,295,500 – $6,808,500). © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: Private Collection, Cologne (acquired directly from the artist).

Schönewald Fine Arts, Xanten & Anthony Meier Fine Arts, San Francisco.

Barbara Mathes Gallery, New York.

Anon. sale, Sotheby’s New York, 9 November 2011, lot 35.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

PROPERTY FROM A EUROPEAN PRIVATE COLLECTION

Literature: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (ed.), Gerhard Richter, Werkübersicht/Catalogue Raisonné: 1962-1993, vol. III, Ostfildern-Ruit 1993, p. 189, no. 720-3 (illustrated, p. 124).

Exhibited: New York, Barbara Mathes Gallery, Gerhard Richter: Works on Paper and Selected Paintings, 2003.

Notes: ‘Abstract paintings are fictive models, because they make visible a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can postulate. We denote this reality in negative terms: the unknown, the incomprehensible, the infinite… Of course, pictures of objects also have this transcendental side to them’ (G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger,Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 314).

‘For Richter, the squeegee is the most important implement for integrating coincidence into his art. For years, he used it sparingly, but he came to appreciate how the structure of paint applied with a squeegee can never be completely controlled. It thus introduces a moment of surprise that often enables him to extricate himself from a creative dead-end, destroying a prior, unsatisfactory effort and opening the door to a fresh start’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 251).

‘It is a good technique for switching off thinking. Consciously, I can’t calculate the result. But subconsciously, I can sense it. This is a nice “between” state’ (G. Richter, quoted in S. Koldehoff, ‘Gerhard Richter, Die Macht der Malerei’, inArt. Das Kunstmagazin, December 1999, p. 20).

Painted in 1990, at the height of Gerhard Richter’s abstract practice, Abstraktes Bild (720-3) is a mesmerising example of the artist’s over painting technique, representing the synthesis of lyrical abstraction and hyper-realism that have been key tenets of his practice throughout his career. Swept across the canvas in vivid kaleidoscopic striations, infinite shades of sapphire blue, emerald green and creamy, white-tempered orange, blend, intermingle and collide, forming a hypnotic panorama of shimmering chromatic strata punctuated by vibrant constellations of primary red and yellow. Textures emerge and dissolve, weaving deliquescent patterns across the densely layered surface. From beneath the polychromatic fabric of the paint, vertical bars painted in Richter’s signature photo realist style emerge, in juxtaposition with the horizontal streaks of marbled colour that surge across the canvas. With its rich palimpsest of prismatic pigment the present work exemplifies the collision of the abstract and concrete, and the balance between chance effects and careful orchestration in Richter’s work. Since 1986, when Richter first took a squeegee to his landscape portraits, the artist has systematically effaced pre-existing works in an act that is symbolic of the artist’s annihilation of the boundaries between the real and fictive, searching for new ways to present the truth in painting. From overpainting photo realist canvases to daubing oil paint on to photographs, the coincidence of abstraction and figuration in Richter’s work explores the tension between illusionistic space and material presence. Loading his canvas with layers of colour before dragging his paint across the canvas, Richter creates a rich continuum of colour that glistens with fluid tactility, the uppermost layer of paint disrupted, revealing the image not quite obliterated beneath. The present work exemplifies Richter’s eloquent command of his medium, cultivated over decades of experimentation in both abstract and figurative registers. His quest to carve a complex space between the two realms is elegantly showcased here: the deliberate over painting of a pre-existing canvas demonstrates the interplay of chance and preparation in the artist’s diverse oeuvre.

Within a body of work relentlessly dedicated to exploring the possibilities of painting, the Abstraktes Bilder were first conceived as a counterpoint to the artist’s already extensive body of figurative photo-paintings. Regarded as one of the finest periods within Richter’s abstract practice, the late 1980s and early 1990s saw the production of significant works including the celebrated Eis cycle of paintings (The Art Institute of Chicago), as well as important examples of hisAbstraktes Bilder series, now housed in important collections including Abstraktes Bild 726 (Tate, London), Abstraktes Bild 727 (Kunsthalle Hamburg) and Abstraktes Bild 734 (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). The early 1990s was also a time of great professional triumph for Richter. His breakthrough retrospective was held at Tate Gallery, London, in 1991, while Documenta IX in 1992 saw the first major presentation of his work in Germany since the showing of 18 October 1977 in Krefeld in 1989. The influential touring retrospective Gerhard Richter: Malerei 1961-1993 opened in 1993, grouping together 130 works in a critically acclaimed exhibition that was to completely transform the artist’s career.

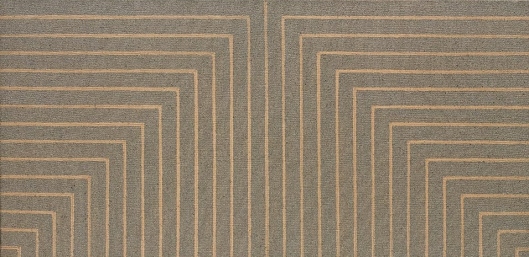

While in many of the artist’s Abstraktes Bilder the underlying illustration is completely sacrificed to Richter’s abstract composition, in the present work the painting that lies beneath is exposed by the skips, schisms and apertures produced by the squeegee as it cuts through gradations of paint, rupturing the diaphanous skeins of colour that proliferate the canvas. This act of erasure illuminates the artist’s manifesto of construction and destruction. Robert Storr writes: ‘Richter’s laconic explanation of this procedure does not emphasize the destruction of what is there for destruction’s sake so much as the erasing of something overly familiar and dissatisfying in the hope that erasure will open the way toward problematic painterly phenomena with unforeseen and unforeseeable consequences’ (R. Storr,Gerhard Richter: Doubt and Belief in Painting, New York 2003, p. 114). Glimpses of illusionistic tubes or bars recall his grayscale curtain and tube paintings from the mid-sixties, which presented his viewers with a structured representation of pictorial space, something that is echoed in the deliberate composition of Abstraktes Bild 720-3. Hinting at a grid-like structure, the loose fabric of the paint traversing the rigidly perpendicular tubes, Richter makes reference to the grid as an important feature that recurs throughout his work, from his 1968 work, Fenstergitter (Window Grid), to the neatly structured organisation of the colour chart paintings and anticipating the grate-like structure of the Cage paintings. Here, in the balance of the abstract and figurative, we see the literal enactment of Richter’s understanding of the two as equivalent: ‘Abstract paintings are fictive models, because they make visible a reality that we can neither see nor describe, but whose existence we can postulate. We denote this reality in negative terms: the unknown, the incomprehensible, the infinite… Of course, pictures of objects also have this transcendental side to them’ (G. Richter, quoted in D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 314).

Adopted by Richter in the second half of the 1980s, the squeegee has been instrumental in Richter’s explorations into the effects of chance in his work. As Dietmar Elger explains, ‘For Richter, the squeegee is the most important implement for integrating coincidence into his art. For years, he used it sparingly, but he came to appreciate how the structure of paint applied with a squeegee can never be completely controlled. It thus introduces a moment of surprise that often enables him to extricate himself from a creative dead-end, destroying a prior, unsatisfactory effort and opening the door to a fresh start’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 251). Richter delights in the automatism of this technique, claiming ‘It is a good technique for switching off thinking. Consciously, I can’t calculate the result. But subconsciously, I can sense it. This is a nice “between” state’ (G. Richter, quoted in S. Koldehoff, ‘Gerhard Richter, Die Macht der Malerei’, in Art. Das Kunstmagazin, December 1999, p. 20). Richter’sAbstraktes Bild 720-3 develops this premise into a sophisticated painterly dialogue between chance and control, exploiting an arsenal of tools in order to blur all traces of the artist’s hand. Using palette knives and different-sized dry brushes alongside the squeegee, Richter scraped, smeared and redirected the random collision of pigments achieved in his initial application of paint. The linear sweep of the squeegee is thus interrupted by fissures, rivulets and faults that obscure the process of the work’s own making. By covering his tracks in this way, Richter creates works that appear before the viewer like naturally-occurring phenomena.

By exploiting the intrinsic properties of paint, Richter has likened his craft not only to natural evolutionary processes, but also to the Duchampian notion of the ‘readymade’. Speaking of his practice at the time of the present work, Richter claims, ‘I’m more concerned now to have [my paintings] evolve of their own accord. I don’t work at random but in a more planned way, in the sense that I let a thing happen by chance, then correct it, and so on. The actual work consists in taking what appears, looking at it then deciding whether it’s acceptable or not. Perhaps this way of working has something in common with the readymade: the artist lets someone else – it doesn’t matter who – do the work of making the object, and the real work lies in observing the thing and deciding whether it’s any good’ (G. Richter, quoted in ‘Interview with Jonas Storsve, 1991’, in D. Elgar and H-U. Obrist (eds.), Gerhard Richter – Text. Writings, Interviews and Letters 1961-2007, London 2009, p. 275). In this way, Richter introduces a conceptual element to his practice, treating paint as a fully-fledged subject in its own right. ‘I hope to achieve the same coherence and objectivity that a random slice of Nature (or a Readymade) always possesses. Of course, this is also a method of bringing in unconscious processes, as far as possible. I just want to get something more interesting out of it than those things that I can think out for myself’ (G. Richter, quoted in ‘Interview with Sabine Schütz, 1990’, in H-U. Obrist (ed.), Gerhard Richter. The Daily Practice of Painting. Writings and Interviews 1962-1993, London 1995, p. 216).

Gerhard Richter (b. 1932), Abstraktes Bild, signed, numbered and dated ‘607-2 Richter 1986’ (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 27¾ x 39 3/8in. (70.5 x 100.1cm.). Painted in 1986. Estimate £1,000,000 – £1,500,000 ($1,513,000 – $2,269,500). © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Vivian Horan Fine Art, New York.

Private Collection.

Anon. sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 11 November 1993, lot 162.

Private Collection, Houston.

Anon. sale, Christie’s, New York, 17 May 2007, lot 181.

Private Collection.

Anon. sale, Christie’s New York, 11 May 2011, lot 66.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (ed.), Gerhard Richter, Werkübersicht/Catalogue Raisonné: 1962-1993, vol. III, Ostfildern-Ruit 1993, p. 180, no. 607-2, (illustrated in colour, p. 100).

D. Elger (ed.), Gerhard Richter, Catalogue Raisonné, vol. III, 1976-1987 (nos. 389-651-2), Ostfildern-Ruit, 2013, p. 525, no. 607-2 (illustrated in colour, p. 525).

Notes: ‘We only find paintings interesting because we always search for something that looks familiar to us. I see something and in my head I compare it and try to find out what it relates to. And usually we do find those similarities and name them: table, blanket, and so on. When we don’t find anything, we are frustrated and that keeps us excited and interested… That’s how abstract painting works’ (G. Richter, quoted in R. Storr, ‘Interview with Gerhard Richter’, inGerhard Richter: Forty Years of Painting, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002, p. 304).

‘Almost all the abstract paintings show scenarios, surroundings and landscapes that don’t exist, but they create the impression that they could exist. As though they were photographs of scenarios and regions that had never yet been seen’ (G. Richter, quoted in ‘I Have Nothing to Say and I’m Saying It: Conversations between Gerhard Richter and Nicholas Serota’, in Gerhard Richter: Panorama, exh. cat., Tate, London, 2011, p. 19).

Rendered in a blazing, fiery palette, spiked with jeweled tones of green, blue and yellow, Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (607-2) bears witness to the exuberant painterly freedom that defined the artist’s output of the mid-1980s. Dazzling in its optical complexity, the work confronts the viewer as a mesmerizing archaeological terrain of texture and colour, a richly layered palimpsest of fissures and collisions. Excavated using an arsenal of tools, the work’s tactile surface bears the marks of Richter’s interventions: scraping, smearing and dragging his paint across the canvas, the artist weaves a hypnotic panorama, using the end of his paintbrush to create linear interruptions in the layers of pigment. Painted in 1986, the work stems from one of Richter’s most experimental and fertile creative periods. After two decades of highly controlled, rigorous painterly investigations, exemplified in his Photo Paintings, Colour Charts and Grey monochromes, amongst others, the 1980s saw the artist embark upon a frenetic exploration of free abstraction. Without pictorial prompts or guidelines, Richter launched himself into a fervent celebration of painting’s contingency, embracing chance and rejecting structured pre-meditation. Painting, in and of itself, became his primary subject matter. The Abstraktes Bilder of this period precipitated an era of professional triumph: with his first major touring retrospectives in Germany and the United States of America, the international art world marvelled at his reassertion of painting’s autonomy. The forty paintings from 1986, many held in collections such as the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Albertina, Vienna, stand as a testament to this newfound liberation. With its sumptuous topography and near-geological strata of paint, the present work is a virtuosic example of Richter’s desire to ‘erase the pictorial object’s function as an illustration of reality and to replace it with the picture’s own reality’ (J. Nestegard,Gerhard Richter: Det Umuliges Kunst, Malerier 1964-1998, exh. cat., Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, 1999, p. 45).

Richter’s intense engagement with abstraction during the 1980s was to transform the face of twentieth-century painting. He had begun his series of Abstraktes Bilder in 1976, cementing the move towards abstraction that had been latent in his earlier body of figurative Photo Paintings. His initial abstract paintings struggled to move away from the supportive framework of photography, using magnified images and photographic sketches as the foundation for his abstract explorations. It was not until the early part of the 1980s that Richter made the seminal move towards free abstraction, allowing the natural evolution of paint across the canvas to dictate the appearance of his works. Yet, unlike the outpouring of energy espoused by his Neo-Expressionist contemporaries, Richter’s efforts retained the calculated nature of his earlier enquiries, and by the time of the present work, his abstract practice had evolved into sophisticated dialogue between chance and control. Though the squeegee, first exploited during this period, generated a certain amount of unpredictability, the end result was always highly mediated by the artist’s watchful eye. Speaking of Richter’s practice during this period, Roald Nasgaard explains how ‘Richter will begin a new group of paintings by placing a number of primed canvases around the walls of his studio, eventually working on several or all of them at the same time, like a chess player simultaneously playing several boards. He begins by applying a soft ground of red, yellow, blue or green… But then it must be altered, with a new move, a first form; a large brush stroke, a track of color drawn out with a squeegee, a geometric shape. Step by step the painting changes in appearance, sometimes sharply, with each new accretion, and goes through several states… They are finished “when there is no more I can do to them, when they exceed me, or they have something that I can no longer keep up with”’ (R. Nasgaard, ‘The Abstract Paintings’ in T. Neff (ed.), Gerhard Richter: Paintings, London 1988, p. 108).

The mid-1980s brought about a period of great personal contentment for Richter, who had married the artist Isa Genzken in 1982. Richter’s gallerist Rudolf Zwirner offered the couple a large studio space Cologne, and the two artists left Düsseldorf behind them – a move that propelled Richter’s rise to international acclaim. In 1986, the year of the present work, Richter was granted his first major touring retrospective at the Städtisches Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf, comprising 133 works and subsequently travelling to the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, the Kunsthalle Bern and the Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna. The critics’ reaction cemented his growing reputation as one of the leading artists of his generation: according to Dietmar Elger, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung named him ‘one of the most interesting skeptics and tacticians of doubt’, whilst Der Spiegel asserted that ‘No one else has explored the potential of painting in an age of mass photography in as coolly engaged and intelligent a manner as he has, or has been as tough and ready to experiment as he is’ (D. Elger, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, Chicago 2009, p. 264). The 1986 retrospective was swiftly followed by an extensive North American exhibition in 1988, touring prestigious locations including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C., and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. By the end of the decade, Richter’s global reputation had soared, paving the way for the career-defining retrospectives of the 1990s.

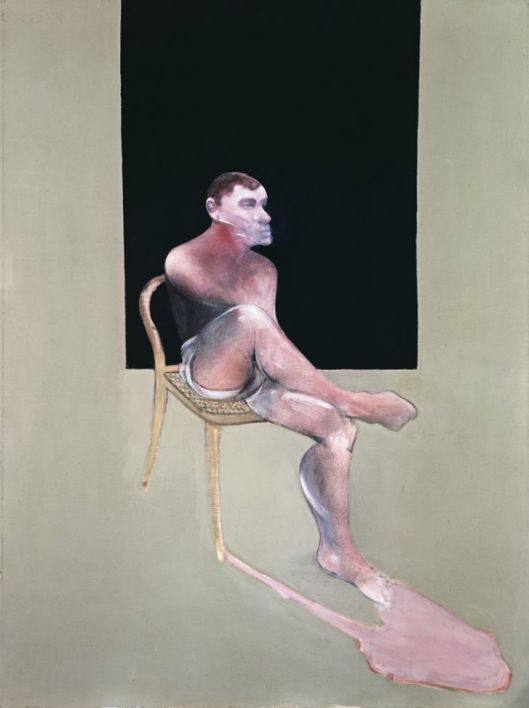

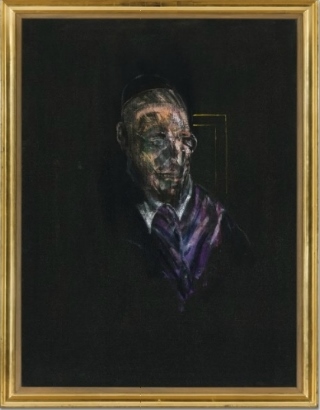

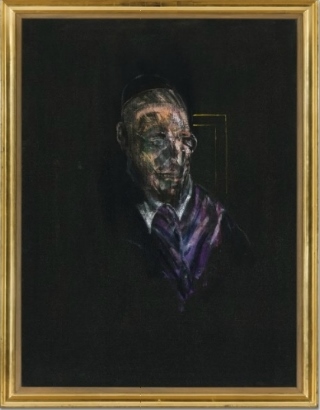

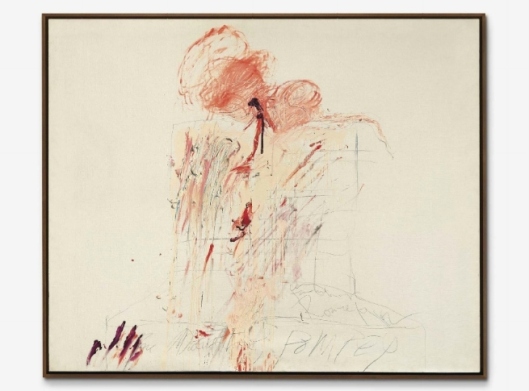

BACON REFLECTS ON POPE PIUS XII

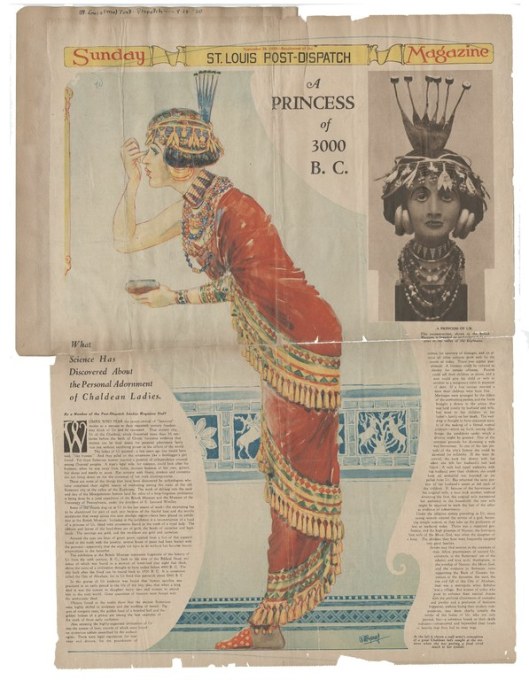

A deeply human portrayal of Francis Bacon’s most enduring subject, Study for a Head, 1955 (estimate on request), is one of only a handful of works depicting Pope Pius XII: the current, living incumbent at the time of the painting. One of the last paintings of Pope Pius XII held in private hands, the others are housed in major museum collections including Pope II, 1951 (Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim), Figure Sitting, 1955 (Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent) and Study (Imaginary Portrait of Pope Pius XII), 1955 (Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich). Fascinated by men of power and authority, Bacon was attracted to the fundamentally tragic combination of violence and vulnerability latent in their status, and sought to capture this paradox in his Papal portraits. Whereas previous works had presented the Pope as a screaming, agonised phantom, Study for a Head presents a figure submerged in existential contemplation, riddled with the same quiet dignity and introspective tension that was to define Bacon’s first self-portrait the following year. Exhibited at Tate, London, in 1962, Study for a Head remained unseen by the public for over 40 years, resurfacing in major retrospectives at the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia, in 2003 and at the Fondation Beyeler, Basel, the following year. Christie’s is pleased to be one of the sponsors of the current exhibition, Francis Bacon and the Art of the Past at the State Hermitage Museum in Russia, which will which showcase paintings from the Sainsbury Centre of Visual Art alongside masterpieces from the Hermitage. This exhibition will travel to Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art in Norwich in April 2015.

Francis Bacon (1909-1992), Study for a Head, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 1/8in. (101.7 x 76.5cm.). Painted in 1955. Estimate Upon Request © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: Hanover Gallery, London.

Mrs. Brenda Bomford, Aldbourne.

Marlborough Fine Art Ltd., London.

Lord and Lady Beaumont of Whitley.

Private Collection, Liege/ Zurich.

Lefevre Gallery (Alex Reed and Lefevre Ltd.), London.

Private Collection, London (acquired from the above circa 1970).

Lefevre Gallery (Alex Reed and Lefevre Ltd.), London (acquired from the above circa 1988).

Onishi Museum, Osaka (acquired from the above circa 1990).

Lefevre Gallery (Alex Reed and Lefevre Ltd.), London (acquired from the above in 1999).

Ernst Beyeler, Basel (acquired from the above circa 2000).

Acquired by the present owner in 2005.

Literature: R. Spira, ‘Londoner Ausstellungen: Francis Bacon in der Tate/Galerie’, in Weltkunst, XXXII, n. 13, Munich, 1 July 1962 (illustrated, p. 17).

R. Alley, Francis Bacon, London 1964, p. 95-96, no. 98 (illustrated, p. 199).

Exhibited: London, Hanover Gallery, Francis Bacon, 1959, no. 6 (incorrectly dated, titled Cardinal, illustrated on the cover).

Nottingham, Nottingham University, Francis Bacon, 1961, p. 1, no. 12 (titled Head of a Cardinal with Glasses).

London, Tate Gallery, Francis Bacon, 1962, p. 38, no. 39 (incorrectly dated, titled Pope). This exhibition later travelled to Mannheim, Städtische Kunsthalle; Turin, Galleria Civica d’ Arte Moderna; Zurich, Kunsthaus and Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum.

London, The Lefevre Gallery, British Paintings 1900-1999, 1999, no. 2 (illustrated in colour, unpaged).

Valencia, IVAM – Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Francis Bacon. Lo Sagrado y lo Profano, 2003-2004 (titled Study for a Head or Cardinal with Glasses, illustrated in colour, p. 74). This exhibition later travelled to Paris, Fondation Dina Vierny, Musée Maillol.

Basel, Fondation Beyeler, Francis Bacon and the Tradition of Art, 2004, p. 360, no. 8A (titled Study for a Head or Cardinal with Glasses, illustrated in colour, p. 344).

Notes: ‘It is true, of course, the Pope is unique. He’s put in a unique position by being the Pope, and therefore, like in certain great tragedies, he’s as though raised onto a dais on which the grandeur of this image can be displayed to the world’(F. Bacon, quoted in D. Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon, London 1987, p. 26).

‘It was during those years [the 1950s], filled with rebuffs and reversals of fortune, but also with extraordinary invention and daring, that Bacon began to explore in depth all his great themes while trying out a number of others that he eventually discarded. It was, in my view, the most fertile single decade of his career. Never again would the Baconian world be so rich and diverse’ (M. Peppiatt, Francis Bacon in the 1950s, exh. cat., Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, 2006, p. 14).

‘No other living painter has set forth with such pitiless clarity the tensions and paradoxes that surround all efforts to see, let alone to paint, the human figure in an age of photography’ (R. Hughes, ‘Singing with the Bloody Wood: A Second Celebration of Francis Bacon’, in Time, 1 July 1985, p. 54).

‘I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them … leaving a trail of the human presence and memory trace of past events’ (F. Bacon, 1955, quoted in Francis Bacon and the Tradition of Art, exh. cat., Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, 2004, p. 233).

Shrouded in silence amidst a deep black void, Study for a Head, 1955, occupies an outstanding position within Francis Bacon’s celebrated series of Papal portraits. A deeply human portrayal of Bacon’s most enduring subject, it stands as one of only a handful of works depicting Pope Pius XII: the current, living incumbent at the time of the painting, who reigned from 1939 until 1958. Where Bacon’s previous Papal portraits had given birth to screaming, agonised phantoms, bordering on caricature in their formal contortions, Study for a Head presents a figure submerged in existential contemplation, riddled with the same quiet dignity and introspective tension that was to define Bacon’s first self-portrait the following year. Mute and alone, animated only by the rapid brushstrokes that chart his worn visage, the figure is isolated upon a vacant ground, engulfed within the dark, cavernous depths of his own psyche. Subsumed by the weight of his grand station, his only anchor within the empty black chasm is a lone corner of gold framing – a stark reduction of the opulent Papal throne upon which he is eternally bound. At a time when the efforts of the Church and the vastly-expanding media cast the Pope as deified patriarch and noble celebrity, upheld before the public on an infallible pedestal, Study for a Head erases the trappings of Papal grandeur, presenting a pale, illuminated face, whose lines, shadows and tensions betray a deep-seated humanity. Bacon was fascinated by processional photographs of Pius being carried through St. Peter’s upon the shoulders of other cardinals, and his rare depictions of this contemporary figurehead include Pope II, 1951 (Kunsthalle Mannheim, Mannheim), Figure Sitting, 1955 (Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent) and Study (Imaginary Portrait of Pope Pius XII), 1955 (Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich). By 1955, here was a man whose reign had witnessed the atrocities of the Second World War, and whose service would come to an end with his death just three years later. Solemnity and grace, terror and resignation, flicker in and out of focus behind his pale glasses, premeditating the mute, incarcerated Papal portraits of the 1960s. Exhibited at Tate, London, in 1962, Study for a Head remained unseen by the public for over 40 years, resurfacing in major retrospectives at the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Valencia, in 2003 and at the Fondation Beyeler, Basel, the following year.

Within the pantheon of Bacon’s oeuvre, the Papal portraits of the 1950s are widely regarded as the paragon of his artistic enquiries, and stand today among the foremost images of the whole of twentieth-century art. The Pope – a man tormented by his position as God’s messenger on Earth – was Bacon’s first and most significant subject, pursued over the course of 53 portraits during a period spanning almost twenty years. ‘It is true, of course, the Pope is unique’, Bacon explained. ‘He’s put in a unique position by being the Pope, and therefore, like in certain great tragedies, he’s as though raised onto a dais on which the grandeur of this image can be displayed to the world’ (F. Bacon, quoted in D. Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon, London 1975, p. 26). The photograph of Pius sat in the artist’s studio alongside images of dictators and henchmen, as well as a reproduction of Diego Velázquez’s immortalPortrait of Pope Innocent X, whose own profoundly human tensions were an important source of inspiration to the series. Fascinated by men of power and authority, Bacon was attracted to the fundamentally tragic combination of violence and vulnerability latent in their status, and sought to capture this paradox in his Papal portraits. His earliest manifestations took the form of screaming ghouls, tortured figures in cages wracked with pain and anxiety. From the inaugural Head VI of 1949, through the first major trio of Popes (I, II and III) in 1951, to the seminal Study after Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X of 1953 and the ensuing series of eight Studies for a Portrait, Bacon’s figures actively sought to escape their condition, depicted as writhing beings whose cries detonated the very structural integrity of the picture plane. By the early 1960s, these ethereal figures had denatured into deformed, demented creatures, incapacitated and silenced by their own paranoia: the Studies for a Pope of 1961 present tensile, muted figures, rooted to their chairs with fear and insanity.

Between these two extremes of hysteria, rarely was the Pope presented with the human compassion of Study for a Head. The work presents a masterful navigation between the twin poles of terror and madness: internalizing the tension of the tormented screaming Popes, the figure radiates a taciturn stillness that anticipates the later, silent half-beings. This is achieved through a subtle distillation of Bacon’s painterly technique. The artist allows liquefied swathes of black paint to soak into the very fibre of the canvas, creating an infinite, impenetrable abyss. On top of this, Bacon crafts his subject’s face with visceral immediacy, in such a way that the face appears to loom outwards like a spectre within the darkness. The rapid articulation of the Pope’s glasses, as well as his mouth, creates microcosmic arenas of tension that amplify the figure’s silence. Vertical striations of paint ram his lips shut, faintly echoing Bacon’s so-called ‘shuttering’ effect: the frenetic linear streaks that screech down the canvas in the earlier screaming portraits. The figure is bracketed by a simple fragment of gold framing. Unlike the gilded thrones represented in the earlier Papal works, the simple, reductive lines that enthrone the present work anticipate the clinical, diagrammatic chairs that subsume Bacon’s later, silent Popes. Bacon’s use of linear framing devices was a constant throughout his oeuvre: often compared to the Chinagraph marks used in photography to delineate areas for enlargement, Bacon construed these lines as formal, perceptual tools. ‘I cut down the scale of the canvas by drawing in these rectangles’, he said, in order to ‘concentrate the image down. Just to see it better’ (F. Bacon, quoted in D. Sylvester, Looking Back at Francis Bacon, London 2000, p. 40). Whilst Bacon’s earlier Popes had used these lines as compositional devices for imprisoning his screaming protagonists, Study for a Head transfers this aesthetic to the Papal throne itself: abstracted and devoid of all ornament, its presence is reduced to a simple geometric fragment. By the Papal works of the 1960s, the slippage between cage and throne was complete: the Pope’s grand seat of power was transformed into an inescapable prison – a straitjacket in which he silently descended into madness.

The use of secondary source imagery was to become definitive of Bacon’s practice, and the Papal portraits were among the first works in which the artist fully embraced this strategy. Working from photographs and reproductions allowed Bacon to access his unconscious, intuitive impulses – to paint from his nervous system, as he put it. ‘I think it’s the slight remove from the fact, which returns me onto the fact more violently’, he told David Sylvester. ‘Through the photographic image I find myself beginning to wander into the image and unlock what I think of its reality more than I can by looking at it’ (F. Bacon, quoted in D. Sylvester, The Brutality of Fact: Interview with Francis Bacon, London 1987, p. 30). In Study for a Head, this strategy allows the artist to transcend the objective, physical facts of his subject, creating a portrait not simply of a man, but rather of his existential condition. Though Pius is ostensibly the work’s subject, the figure’s appearance is heavily mediated by the visual properties of Velázquez’s portrait: the side-on angle, framed by the Papal throne, as well as the white collar and opulent purple robes – Bacon’s transmutation of Velázquez’s deep crimson. Across the breadth of the Papal works, individual features of Pius and Innocent oscillate and collide, shifting in and out of focus to produce a kind of hybrid archetype: a powerful Papal specimen filtered through the depths of Bacon’s own visual memory. Other visual sources enter the fray: indeed, the glasses that feature here and elsewhere are themselves a composite concoction, inspired as much by Pius himself as by the iconic film still of the screaming nurse in Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Bacon’s archive of source material, ranging from Poussin to contemporary newspaper clippings, provided a visual reservoir that allowed him to move beyond the simple act of representation, creating prototypes and paradigms of human emotion through multiple, serialised iterations. In 1955, the year of the present work, the artist described how ‘I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them … leaving a trail of the human presence and memory trace of past events’ (F. Bacon, 1955, quoted inFrancis Bacon and the Tradition of Art, exh. cat., Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna, 2004, p. 233).

Bacon’s desire to depict the Pope’s humanity in Study for a Head is coterminous with his expanding exploration of the human condition in its broadest sense, exemplified by the corpus of non-Papal portraits from the late 1940s and 1950s. Indeed, the Papal works themselves have their roots in Bacon’s earliest Head series, with Head VI standing as the first surviving example. Throughout the 1950s, the production of Papal works was matched by an equally prolific output of portraits that, like the present work, were isolated within thick black voids, brooding with existentialist tension. Portraits of friends and early patrons, including the collectors Robert and Lisa Sainsbury whom Bacon first met during this period, were set within the same deep, dark chasms, silently pensive and imbued with contemplative dignity. It was also at this time that Bacon began his seminal Man in Blue series: arguably the secular, capitalist counterpart to the Popes, these works cast their protagonist as a museum-like relic, framed and spotlit within the metaphorical display cabinets of Bacon’s own psyche. This vernacular, with its subtle overtones of memento mori, also lay at the heart of Bacon’s Studies after the Life Mask of William Blake which are contemporary with the present work. The series presents eerie incarcerations of the visionary poet’s once-living head, preserved for eternity as a sculptural mould and illuminated within the dark abyss of time. Study for a Head, with its compositional austerity and aura of clinical examination, must undoubtedly be seen within the context of Bacon’s 1950s portraiture. Stripped of his divinity, the Pope is reduced to a specimen of humanity, placed on trial before his public as an object of scrutiny and marvel.

Significantly, it was within this compositional mode that Bacon undertook to represent himself in paint for the first time, the year after the present work. It has often been posited that the Papal portraits masquerade as self-portraits of sorts, much in the same way that Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele painted themselves in the guises of prophets, priests and martyrs in order to interrogate the psychological anxieties of their time. The post-War era was marked by a fundamental questioning of humanity: its representations and systems of belief. The Existentialist philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre, which rose to prominence during the 1940s, found their visual complement in ethereal figural sculptures of Giacometti: stark, elongated visions of the human form, reduced to their bare linear essentials. Imprisoned in the Cageworks of 1950, in a manner similar to Bacon’s own graphic framing devices, Giacometti’s sculptures contemplated the very substance of being precariously balanced on the brink of eclipse. For Bacon, the turmoil of the post-War era was matched by his own emotional turbulence. It was during the 1950s that his tempestuous relationship with Peter Lacy ran its course, reaching its denouement shortly after the present work. A former Spitfire pilot, Lacy’s persona embodied the same combination of brutality and vulnerability that drove Bacon’s fascination with figures of authority during this period. The artist’s troubled memories of his domineering father also loomed large in his memory at this time, and his portraits of the Pope – the ultimate Papa – were frequently strewn with the likeness of his own patriarch. In Study for a Head, Bacon presents a man whose identity is on the brink of dissolution. His tense lips strain to voice his predicament, yet silence prevails; trapped within the dark recesses of Bacon’s canvas, he stands as an illusory vestige of the artist’s own imagination.

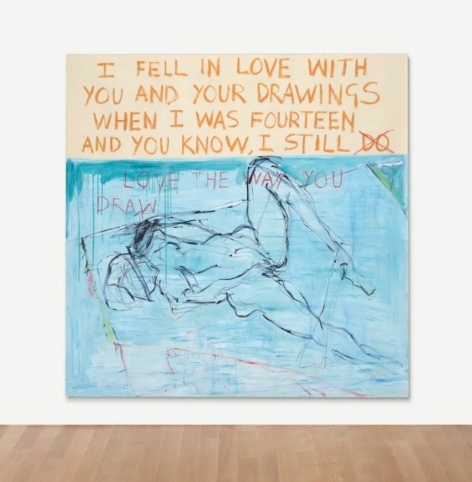

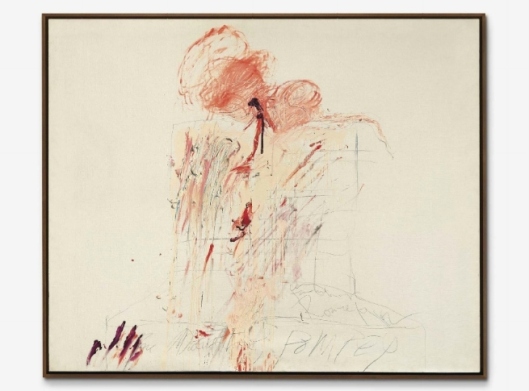

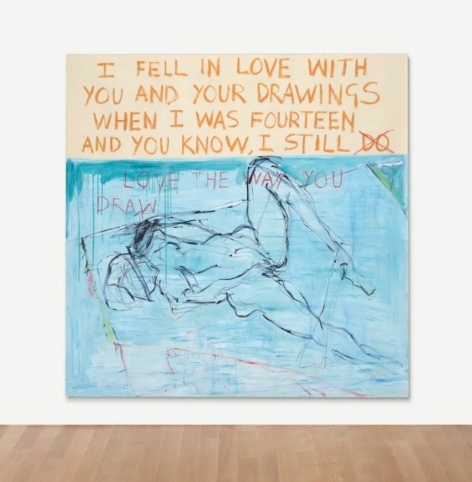

TRACEY EMIN EXORCISM OF THE LAST PAINTING I EVER MADE

Following the success of Tracey Emin’s iconic My Bed, 1998, which achieved a world record price at auction quadrupling its pre-sale estimate to realise £2,546,500/ $4,351,969/ €3,178,032 (estimate: £800,000-1,200,000) in July 2014, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, 1996 (estimate: £600,000 – 800,000), documents a seminal moment of breakthrough within the artist’s oeuvre, witnessing an impassioned re-engagement with her painting and drawing practice after a six-year hiatus. Over a three week period Emin barricaded herself into a room at the Galleri Andreas Brändström, Stockholm, where, working completely naked, she launched herself into a frenetic artistic outpouring. Comprising 105 paintings, body paintings, drawings and letters, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made lays bare Emin’s entire artistic make-up, paying homage to her influences including Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele and Yves Klein. Emin’s paintings and drawings have since come to represent one of the most significant strands of her oeuvre, culminating in her appointment as Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 2011, and will be celebrated in the exhibition Tracey Emin – Egon Schiele: Where I Want to Go at the Leopold Museum, Vienna, in April this year.

Tracey Emin (b. 1963), Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, installation including 12 paintings, 7 body paintings, 79 works on paper, 7 letters, numerous painted items, art supplies, personal items, 1 bed and mattress and various other items of furniture, 1 radio and CD player, 9 music CDs, various newspapers and magazines and numerous kitchen and food supplies; dimensions variable. Executed in 1996. Estimate £600,000 – £800,000 ($907,800 – $1,210,400). © Christie’s Images Ltd. 2015.

Provenance: Galleri Andreas Brändström, Stockholm.

Anon. sale, Christie’s, London, 8 February 2001, lot 30.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: B. Riemschneider and U. Grosenick (eds.), Art at the Turn of the Millennium, Cologne 1999 (Cologne version of the installation illustrated in colour, p. 149).

T. Warr (ed.), The Artists’s Body, London 2000, p. 68 (installation view illustrated in colour, p. 69 and on the cover).

Saatchi Gallery (ed.), 100: The Work that Changed British Art, London 2003, p. 209, no. 43 (illustrated in colour, p. 99).

H. Luard and P. Miles, Tracey Emin, London 2006, p. 220 and 413 (installation view, ‘Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made 1996’ illustrated in colour, pp. 221-224).

N. Brown, TE Tracey Emin, London 2006, p. 88 (installation view, ‘Naked Photos: Life Model Goes Mad 1996’ (illustrated in colour, p. 89).

Love is What You Want, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery, London 2011, p. 248 (installation view, ‘Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made’ illustrated in colour, p. 248).

Exhibited: Stockholm, Galleri Andreas Brändström, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, 1996.

London, South London Gallery, I Need Art Like I Need God: Tracey Emin, 1997 (installation view, ‘Naked Photos: Life Model Goes Mad 1996’ illustrated in colour, pp. 38-39 and on the cover).

Cologne, Kölnsicher Kunstverein, Ca-Ca Poo-Poo, 1997-1998.

Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Ten Years, Tracey Emin, 2002.

Edinburgh, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Tracey Emin: 20 Years, 2008 (installation view, ‘Naked Photos: Life Model Goes Mad 1996’ illustrated in colour, nos. 23-25, installation view, ‘Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made 1996’ illustrated in colour, no. 26). This exhibition later travelled to Malaga, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo and Bern, Kunstmuseum.

Notes: ‘Many artists have used female nudes in their work. I’ve got a good female nude I can use whenever I like and its mine … I’m my own muse. And it’s so liberating to be naked. You have a better sense of your own being’ (T. Emin, quoted in C. Freedman (ed.), Tracey Emin: Works 1963-2006, New York 2006, p. 166).

‘You might think Klein was being sexist by using those models like that, but actually it was something remarkable. Those women were not “muses”, they were dancers, and he was like a choreographer and there was a fantastic skill involved’ (T. Emin, quoted in J. Wainwright, ‘Interview with Tracey Emin’, in M. Merck and C. Townsend (eds.), The Art of Tracey Emin, London 2002, p. 197).

‘I knew when I was doing the Yves Klein and they [the audience] didn’t know I was going to do it. I heard a stampede across the gallery and “she’s doing an Yves Klein!” – all these people fighting to get at the portholes’ (T. Emin, quoted in J. Wainwright, ‘Interview with Tracey Emin’, in M. Merck and C. Townsend (eds.), The Art of Tracey Emin, London 2002, p. 198).

‘It was about being stripped and it could have been about being vulnerable but actually it wasn’t, it became about the ego and about the strength of the ego. The strength of my failures are all amalgamated together. It was called Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made because it was for me to get rid of them, plus the fact that painting for me was completely moribund: it was completely bound up with failure. Failure – painting, painting – failure: two things joined together which I wanted to separate’ (T. Emin, quoted in J. Wainwright, ‘Interview with Tracey Emin’, in M. Merck and C. Townsend (eds.), The Art of Tracey Emin, London 2002, p. 198).

‘I have never not drawn, I have been drawing all my life’ (T. Emin, quoted in interview with A. Elkann, 11 December 2014, http://alainelkanninterviews. com/tracey-emin/ [accessed 5 January 2014]).

‘I am my own model. When you look at Picasso I am sure he used his own body as a model, all the women are square like he was. But then my favourite artists are Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele and they used themselves constantly in their work. So did Rembrandt and van Gogh’ (T. Emin, quoted in interview with A. Elkann, 11 December 2014, http://alainelkanninterviews.com/tracey-emin/ [accessed 5 January 2014]).

‘[Edvard Munch’s The Scream is] an incredible piece of work, and it needs to be championed for what it is, for its integrity. Someone painted the sound of a scream. People think it’s the figure screaming, but maybe it’s nature screaming at the figure’ (T. Emin, quoted in The Guardian Weekend, 12 October 2002, p. 32).